Our Verdict

A startlingly unnecessary CPU, one that only serves Intel's own designs and not actual PC gamers. Its specs feel weaker than the last-gen flagship, it's more expensive, and has a thirstier core at its 14nm heart.

For

- Unlocked almost on par with 10900K

- Slightly faster gaming fps than AMD

Against

- Weak PCIe 4.0 performance

- Core i9 specs downgrade

- Unnecessarily expensive

PC Gamer's got your back

This isn't the Intel Core i9 11900K we were supposed to have. The very heart of this processor is fundamentally different from the one that was meant to have beat out a rhythm for Intel's 11th Gen Core CPUs, and that, in the end, is why I doubt anyone will feel comfortable recommending this nominally $539 CPU. I certainly don't.

The Rocket Lake range of CPUs was in trouble from its inception, and that rings especially true for the Core i9 11900K as the flagship chip of this new generation of desktop processors. From the very first decision to create this set of CPUs, Rocket Lake was always on the back foot, because Intel's failure is the only reason for its existence.

Tiger Lake. That's what we should be writing about when it comes to this 11th Gen series. That's what we're doing on the mobile side of Intel's business, even the high-performance, gaming-focused chips that are coming out later in the year. But, instead of that continuation of the 10nm production process into desktop form, Rocket Lake is another 14nm chip, but one that is trying to take the previous 10nm core design and fit it into 14nm silicon.

It's not quite a square peg in a round LGA socket, but it's the reason why Rocket Lake is such a jarring CPU generation at the top end.

Architecture

What's different about the Intel Core i9 11900K

The first thing to note is that Rocket Lake isn't Tiger Lake's 10nm core back-ported into a 14nm CPU package. The Cypress Cove core architecture that powers the Core i9 11900K is essentially the Sunny Cove design squeezed into a chip that can fit in the same socket as the old Comet Lake Core i9 10900K. That was the 10nm design used in the Ice Lake generation of laptop CPUs, while Tiger Lake uses a further refined Willow Cove core, one with fresh transistors optimisations, a redesigned cache system, and higher IPC.

The second thing to note is why a back-port was needed in the first place, and this is something for which I still haven't got a satisfactory answer out of Intel.

There's nothing more Intel can squeeze out of the geriatric Skylake core

The basic situation is that Intel's shift to broader 10nm manufacturing has been significantly impacted by production issues, first around the initial Cannon Lake chips—which barely made it out of the fabs—and constrained by further yield problems with the subsequent Ice Lake design. Neither CPU architecture was then capable of pushing the high frequencies required of modern desktop processors and so those remained stuck on the 14nm node, and on modest iterations of the original Skylake core design from 2015.

But Intel couldn't spin out another version of the 14nm Skylake architecture for its early 2021 chip release if it wanted to catch up to AMD's excellent Ryzen 5000-series CPUs. The latest Zen 3 CPUs have either caught up to, or surpassed, Intel's comparative processors when it comes to gaming performance, and there's really nothing more Intel can squeeze out of the geriatric Skylake core to push ahead.

So the decision was made to bring the Sunny Cove design into one final 14nm CPU range, thus Rocket Lake was born. This would have likely been made while the Willow Cove core for Tiger Lake was being finalised and so the latest 10nm design was probably never really considered for the 11th Gen desktop architecture.

This wouldn't have been a decision Intel took lightly; there will always be sacrifices engineers have to make in order to retool such a core for 14nm production. The most obvious of which concerns space. The problem is that, while a 10nm core can be smaller than a 14nm design if it's fundamentally the same, just on a smaller node, Sunny Cove, and by extension Cypress Cove, are different. Intel originally used the more diminutive process to jam more logic into the cores and the result is that by going back the engineers have had to scale back the Core i9 chip.

The most notable casualty is the core count. There was no way for Intel to maintain the same ten-core design as the i9 10900K with the fatter Cypress Cove cores and still be able to fit in the new Xe GPU. Why bother if we're just going to be strapping discrete graphics cards to these CPUs anyway? Well, there's a vast industry for Intel in shipping chips out to corporate clients which rely solely on the integrated graphics of its processors and it would be too expensive to manufacture wholly different cores.

There are still F-series Rocket Lake chips that lack integrated graphics, but those simply have disabled GPU cores, and aren't different CPUs with a gap where the 32EU Xe silicon should be.

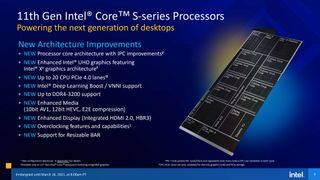

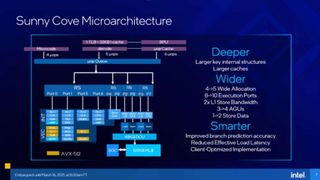

The big idea behind Cypress Cove is the same as Sunny Cove: Deeper, Wider, Smarter. There is a greater amount of cache at different levels of the chip, with more L1 Data cache and more L2 cache than with Skylake.

There's still the same 2MB of L3 cache per core, so that 'Smart Cache' number doesn't change with Rocket Lake. Intel has also broadened some key facets of the microarchitecture too, but we'll start getting into names of things that us PC gamers probably don't need to worry overmuch about, such as reorder buffers and execution ports. Suffice to say there are more of them.

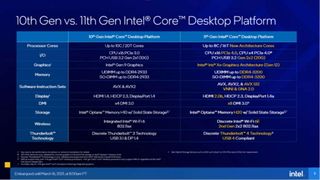

And the end result is an architecture which delivers higher instruction per clock performance—which Intel is claiming at around 19 percent over Comet Lake—a hardware fix to the security flaws (such as Meltdown), more PCIe lanes from the CPU (and those running at PCIe 4.0 speeds), and greater memory speed.

It's an obviously bigger chip design compared with the last-gen Comet Lake CPUs, thanks to having to expand to 14nm. But that scale up doesn't just impact the physical size, it has an obvious effect on the amount of power the less-efficient process demands. In short, Rocket Lake is thirsty. And that's another compromise Intel's engineers have had to make with the Core i9 11900K, the Sunny Cove back-port, and its slightly enhanced version of the 14nm+++ node.

Specs

What's inside the Intel Core i9 11900K?

As the flagship processor of the Rocket Lake lineup the Core i9 11900K is all that the 11th Gen desktop can be. Which is to say a nominal downgrade on the best of the 10th Gen chips. The key spec for the i9 11900K is the core-count, and at eight cores and 16 threads that's lower than the cheaper i9 10900K. That's going to be a tough sell for Intel this time around.

Cores: 8

Threads: 16

Base clock: 3.5GHz

All-core boost: 4.7GHz

Single-core boost: 5.3GHz

Smart cache: 16MB

TDP: 125W

Memory support: DDR4-3200

Price: $539

In terms of clock speed, we're also looking at a chip that's slower than its last-gen brethren. Its peak of 5.3GHz is the same as the i9 10900K, and matches it by also being mostly unable to actually nail that speed for more than a pico-second here and there. The base frequency, however, is lower, which scarcely matters either. The top and bottom of Intel's frequency numbers are almost irrelevant because you'll never really see your chip operating at those limits.

What's more important is the all-core turbo number, and at 4.7GHz the eight-core Rocket Lake chip is again slower than the 4.8GHz of the ten-core Comet Lake CPU. It also has a tendency to swiftly throttle back to around 4.3GHz thanks to the Intel power limits.

But hey, at least this advanced processor can fit in the same LGA 1200 socket as the 10th Gen CPUs. Though then you're missing out on the thing that feels the most like a tangible upgrade for Rocket Lake, the PCIe 4.0 support. Now, a lot of last-gen Z490 motherboards are getting BIOS updates to allow for PCIe 4.0 support with an 11th Gen CPU, and many have already had them, but Intel has also released the Z590 chipset with baked in PCIe 4.0 support.

The Z590 chipset itself, however, is still resolutely running on PCIe 3.0, making support still feel like Intel's only put a solitary butt cheek into this. With 20 PCIe 4.0 lanes coming from the Rocket Lake CPU alone, there is just enough for a full x16 GPU slot and a single x4 NVMe SSD. Admittedly you can happily run your GeForce RTX 3080 or Radeon RX 6800 XT on a PCIe 4.0 socket running at x8 speeds as it will still have the same bandwidth as a full x16 PCIe 3.0 slot, but it is most definitely a limitation moving forward.

The TDP of the Core i9 11900K is the same 125W as the Core i9 10900K, though if you dig a little deeper you'll see that actually Rocket Lake's top eight-core chip has a secondary power limit (PL2 for short bursts of higher frequencies) that is higher than the ten-core Comet Lake, particularly the base level where it's 203W versus 177W.

Benchmarks

How does the Intel Core i9 11900K perform?

You may well have gotten this far through my review wondering what the hell the point was for Intel going to all the effort of back-porting Sunny Cove to 14nm only to create what looks like a worse CPU on paper. After all, the actual back-porting process was not an easy thing for the Israel arm of Intel's engineering team to do, and the fact that it has created Rocket Lake at all is still an impressive feat.

The 11900K beats the 5900X, our favourite CPU right now, when it comes to gaming

But it was also important to Intel as a whole, because with the Core i9 11900K it can once more claim to have the fastest gaming CPU in the world. Forget the limitations of the eight-core design when it comes to multithreading performance against the Core i9 10900K and AMD's Ryzen 9 5900X—the chips it most closely rivals—because it can outgun them both in games.

Though only by a borderline irrelevant amount, it's still there in benchmark numbers, in easy to parse frames per second figures: The Core i9 11900K beats the Ryzen 9 5900X, our favourite CPU right now, when it comes to gaming.

In everything besides Shadow of the Tomb Raider, it's only ever by a mere handful of frames per second. The delta is small enough that you could almost put it down to variance in testing, but it is so consistently on the side of the Intel chip that I feel pretty confident in stating that the Core i9 11900K is the more able of the two. Only the F1 2019 benchmark has the Ryzen 9 5900X with a 4 fps advantage.

Gaming performance

The story is, inevitably, completely different when it comes to literally anything outside of gaming. The Ryzen 9 5900X, and honestly the Core i9 10900K too, is far superior when it comes to actual, y'know, processing. Obviously, the higher core counts of those two chips give them much greater multithreaded performance, and that's born out by the x264 video encoding and Cinebench rendering figures. The Ryzen 9 5900X delivers 68 percent and 45 percent higher scores respectively in those two tests.

Even if you unlock the Intel power limits—which pretty much every Z590 motherboard will do with a single setting in the BIOS—and enable Adaptive Boost Technology, giving the Core i9 11900K all the rope it needs to hang itself, it still falls well short of the equivalently priced Zen 3 CPU. In fact, even though that allows it to stick resolutely to a 5.1GHz all-core clock speed, it's still just behind the Core i9 10900K.

To be fair, that does mean that with the Intel shackles removed from the Rocket Lake chip (shackles there to allow Intel to call it a 125W processor) those eight Cypress Cove cores are able to offer almost the same multithreaded performance as the ten Skylake cores of Comet Lake. Which is an impressive, if supremely thirsty feat.

Platform performance

Intel motherboard: Asus ROG Maximus XIII Hero

Chipset: Z590

AMD motherboard: Gigabyte X570 Aorus Master

Memory: Corsair Vengeance RGB Pro 32GB @ DDR4-3200

GPU: Nvidia RTX 2080 Ti

Storage: 2TB Kioxia Exceria Plus

CPU Cooler: Corsair H100i RGB Pro

PSU: NZXT 850W

Chassis: DimasTech Mini V2

Monitor: Philips Momentum 558M1RY

And that does speak to the architectural improvement the Sunny Cove back-port offers. That was something we tested by artificially levelling the playing field and locking both the 10900K and 11900K chips at 5GHz and with eight cores operational.

We only saw an 18 percent IPC increase from a single core Cinebench R20 run. And that absolutely does not translate to games, with game performance seeing generally far less than a 6 percent increase by virtue of the update to Cypress Cove.

Power is the fizzling Edison elephant in the room, however. The Cypress Cove back-port, as I alluded to earlier, is incredibly thirsty when it comes to its power requirements. If you leave the standard power limits in place then the Core i9 11900K runs with 19 percent higher power levels than the 12-core AMD chip, and if you remove those power cuffs the delta jumps to 80 percent higher.

What about overclocking? Yeah, that's what I'd like to know too

And what about the shift to PCIe 4.0 support? Right now, that's a bit of a struggle. Ahead of the release, with the Asus motherboard BIOS Intel supplied for the Maximus XIII Hero, the SSD performance of Gen4 drives seems pretty far off the level set by AMD's Ryzen 5000-series. It's possible that the synthetic benchmarks we use aren't working perfectly with the new Intel platform ahead of release, but AS SSD and ATTO are well below where the same Sabrent Rocket 4.0 Plus drive performed on Zen 3.

The PCMark 10 storage tests, however, do show an improvement for Intel, as does the straight 30GB file copy test. The game level load time benchmark, using the FFXIV: Shadowbringer test, however, highlights a dip. Which to believe? To be honest, this seems like the most immature part of the platform, and I feel like the SSD performance alone is likely to change a lot over the next few months.

What about overclocking? Yeah, that's what I'd like to know too. I got nothing out of my sample. Where I could get the Core i9 10900K comfortably running with a 5.3GHz all-core clock speed by undervolting it, and even a little flakier at 5.4GHz, this Rocket Lake chip is having none of it.

Crashes or suddenly aggressive power limits kick in, even when the shackles are supposedly off. Undervolting doesn't help, and I think this is something I'm going to have to revisit a few BIOS updates down the line.

Analysis

What does the Intel Core i9 11900K mean for PC gaming?

The Core i9 11900K seems to exist solely so Intel can tell people it has the world's fastest gaming processor again. Our performance metrics do bear that claim out, but the numbers are only just in Intel's favour compared to our favourite AMD chip, the Ryzen 9 5900X. That means game performance can't really be a defining factor when the time comes to choose your next CPU.

That only really works if everything else is equal, and that's not the case with this generation. Certainly, it's tough for me to recommend the Core i9 11900K purely on the back of its slight gaming performance lead considering the breadth of platform that AMD currently offers.

The only struggle for the red team, and the one place where Intel might be able to garner a little positivity around Rocket Lake, is in the fact that the Ryzen 9 5900X has been in mighty limited supply for much of its life. Everything in PC gaming has been in short supply it seems, though in processor terms things have been nowhere as sticky as in the graphics card market, and there are definite signs of a recovery for the other Zen 3 CPU stocks.

The mighty mainstream hex-core Ryzen 5 5600X is back on sale again at $350 and the eight-core Ryzen 7 5800X is in stock too at $490. If the 12-core, $550 Ryzen 9 5900X was available it would 100 percent be the CPU to beat, something the Core i9 11900K only does by a hair in gaming.

But it's not available, and so what about compared to the eight-core Ryzen 7 5800X? That's got a similar level of general processing performance, if not a touch more, and is roughly on par when it comes to gaming too, if not a little lower. It is a lot cheaper though, comes with full PCIe 4.0 support across the entire platform of CPU and chipset, and isn't going to be quite so demanding of your PSU for full-fat performance.

So, that still feels like a more reasonable chip to chase than the newly released Rocket Lake processors.

What if you need a little more at the high-end though? What if you crave the promise the extra core count of the Ryzen 9 5900X offered, but can't go all the way up to the now ludicrously expensive Ryzen 9 5950X? This is where Intel has a shot, and in part that's thanks to Rocket Lake.

Because the new Intel 11th Gen chips have been newly minted the older 10th Gen CPUs, which are still in pretty healthy stock thanks to a genuine AMD alternative evening out demand, are available for a great price now. The Core i9 10900F, a ten-core, 20-thread chip with a high clock speed, is the same $350 as the six-core, 12-thread Ryzen 5 5600X.

It still feels like there's no place for Rocket Lake at the high end, though. Honestly, it's a good thing the company timed its big Intel Unleashed event before the release of these 11th Gen desktop chips because based on the Core i9 11900K you'd be forgiven for looking at Intel as though it had completely lost its way. I'd certainly have less hope it could find a path back without Pat Gelsinger's confident keynote the other day.

Rocket Lake brings nothing new to the table for all its smart retrograde engineering

Back-porting its 10nm architecture to fit with its mature 14nm manufacturing prowess probably seemed like a smart roll of the dice when it was first mooted, but the reality of that decision has revealed a flagship CPU that offers a solution to a problem that doesn't exist for anyone but Intel. It's Intel that needed a chip to catch or beat AMD's rejuvenated Zen 3 gaming metrics, not us.

Comet Lake trades blows with AMD, and we've spoken about how little impact the CPU has on frame rates in real terms. So either of the 10th Gen or 5000-series chips will deliver on those counts. So Rocket Lake brings nothing new to the table for all its smart retrograde engineering.

Apart from, that is, lower down the stack. Back in the before time, the long, long ago, when Intel was dominant, we would laud the power of the Core i7 (then the top of the line) but recommend the Core i5 as the one most gamers should go for. Now the Core i5 is the only Rocket Lake anyone should go for.

That's a chip which improves on its forebear on every level, comes in at the right price, and generally tops its AMD hex-core equivalent in the bargain.

The part I still don't really understand is why Tiger Lake itself wasn't an option. Was it simply down to the volume of high-performance 10nm chips that it would need to produce in order to fulfil both the demands of gaming laptop and desktop users? Could Intel not trust its 10nm fabs to deliver all it needed? Or was there some specific reason it had to get a new chip generation out at the start of year?

I guess the knowledge that Alder Lake was on the way at the end of 2021 meant any other release timing would bump too close into that launch, so if Intel could rely on delivering the 10nm Tiger Lake architecture to desktops, but not until the Summer, maybe that's why it was off the cards. It's certainly not because the silicon can't hit the clock speeds desktop users demand, as the promised Tiger Lake H CPUs are set to drop into laptop land with up to eight cores, 16 threads and 5GHz+ frequencies.

Those sound like pretty good numbers for an 11th Gen desktop chip if you ask me, and would offer an IPC bump even over Cypress Cove, would sit in a smaller package, and be far more power-efficient than Rocket Lake is capable of.

For me, taking the backwards step of releasing a Core i9 with fewer cores than the last generation, but for a higher price, exemplifies that traditional Intel hubris, making it seem as though the company has learned nothing from the inexorable rise of Ryzen. If Intel had swallowed its pride, eschewed the i9 tier just for Rocket Lake, and simply made this its $399 octa-core i7, it would have been a far more welcome addition to the market.

Instead, it's saddled the i9 with an unreasonable price tag and hobbled the i7.

Verdict

Should you buy the Intel Core i9 11900K?

The Core i9 11900K as the world's fastest gaming processor is a fine title to present to your investors, and maybe even help to temporarily add a couple of points to your bottom line, but for us PC gamers it's become an almost irrelevant claim. With your GPU having so much more impact on gaming frame rates than your CPU, these days having the world's fastest gaming processor feels a little like being able to say you've got the lightest SSD or the most waterproof graphics card in your desktop rig.

In the end, for gaming, your CPU really just needs to be good enough to allow your graphics card to flex, and that means your decision comes down to what else a chip can offer. And in those terms, AMD's Ryzen 5000-series processors have far more in their lockers.

The Core i9 11900K only has a few frame rate wins to show for itself. It's not tangibly quicker than the last-gen i9—in fact, it's notably slower in multithreaded processing power—has a weaker specs sheet, costs more, and is far more thirsty. And Comet Lake itself was already pretty demanding on that front.

As the first PCIe 4.0 compatible Intel platform, it's also a disappointment as it can only offer support from the CPU itself, not the chipset. And even then the performance looks pretty dismal right now.

On the AMD side, however, you have options for greater core counts, effectively the same level of gaming performance (what's a few fps between friends?), a more mature PCIe 4.0 enabled platform, and more affordable eight-core chips to offer. And when the Ryzen 9 5900X comes back into stock, AMD has the best all-round CPU offering there is.

The answer then is: No. You shouldn't buy a Core i9 11900K, because there are objectively better chips on offer from AMD or even Intel's previous generation.

A startlingly unnecessary CPU, one that only serves Intel's own designs and not actual PC gamers. Its specs feel weaker than the last-gen flagship, it's more expensive, and has a thirstier core at its 14nm heart.

Dave has been gaming since the days of Zaxxon and Lady Bug on the Colecovision, and code books for the Commodore Vic 20 (Death Race 2000!). He built his first gaming PC at the tender age of 16, and finally finished bug-fixing the Cyrix-based system around a year later. When he dropped it out of the window. He first started writing for Official PlayStation Magazine and Xbox World many decades ago, then moved onto PC Format full-time, then PC Gamer, TechRadar, and T3 among others. Now he's back, writing about the nightmarish graphics card market, CPUs with more cores than sense, gaming laptops hotter than the sun, and SSDs more capacious than a Cybertruck.